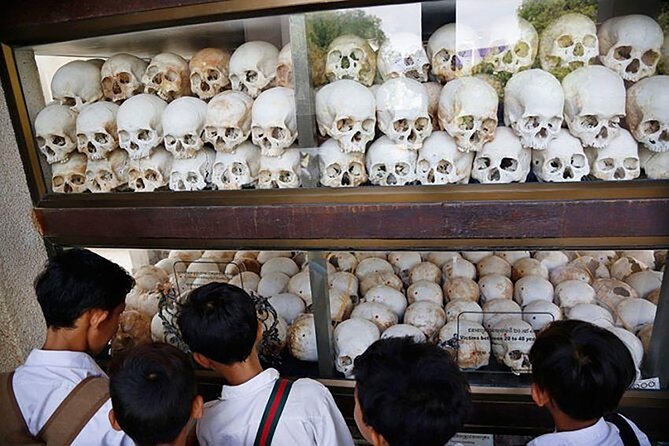

Hundreds of thousands of tourists visit the killing fields and the Khmer Rouge’s infamous S21 prison every year. Sadly, “genocide tourists” take little more away from this awe-inspiring, ancient land than the remembrance of savagery. Before and after my visit alongside thousands of other Western tourists, I sought to go deeper into who the culprits of this barbarism were.

A Return to the Killing Fields

Predictably, these grim “museums” do little to properly contextualize what happened in Cambodia from 1975-1979. This is by design; like the media and schools, museums have a specific ideological function.

The dominant narrative surrounding the Cambodian genocide is that the horrific slaughter of an estimated two million of Cambodia’s eight million people was prosecuted by a lone, crazed, megalomaniac dictator, Saloth Sar. “Pol Pot” was Sar’s underground nom de guerre that he adopted in the guerilla struggle. We know him by this name in the West. Individuals, however, do not make history on their own but rather operate within the context of the historical conditions they inherit. There was more in motion in Cambodia than one renegade madman.

The historians of the ruling class have sinisterly turned the anti-Khmer Rouge (which means Red Cambodians) narrative into an anti-communist narrative. Conflating Pol Pot’s world view with communism is all too convenient for the ruling class but it is a gross perversion of the truth.

Marxists seek a deeper understanding of the Cambodian genocide than the one Hollywood spoon-feeds us.

The U.S. Holocaust

In an attempt to crush the Vietnamese National Liberation Front, the U.S. secretly dropped 500,000 tons of bombs on Cambodia, the equivalent of five Hiroshimas. What was a “secret” in the West was a genocidal reality for millions in the real world. In five months of “carpet bombings” in 1973, U.S. planes dropped over 240,000 tons of bombs, destroying the farming areas of the Mekong River. Half a million U.S. troops carried out search and destroy missions across Vietnam against NLF fighters.

These crimes produced thousands of “killing fields” and forced millions of peasants to take refuge in Cambodia’s main city Phnom Penh. By all estimates, between 3 and 5 million Khmers, Laotians and Vietnamese were killed by the U.S. war. Thousands of villages and families were incinerated by high-tech U.S. bombs like napalm and agent orange. To this day there are hospitals and communities affected by the U.S. bombs which the author was able to visit. Children are still born with birth defects from the chemicals left by Agent Orange.

In his visit to Laos in 2016, President Obama himself recognized that thousands of U.S. bombs still lay unexploded in the countryside and continue to maim farmers.

The U.S. war of aggression against Vietnam and its neighbors was one of the greatest crimes of the 20th century. Why isn’t this called a holocaust?

If we do not understand the original crimes perpetrated by the U.S. military, little else will make sense in the region.

The Evacuation of Phnom Penh

More than half a million Cambodians were killed by U.S. bombing. Scarcity and hunger were already a problem because of the brutal feudal system. The U.S. war ruined the already weak agricultural system. Facing starvation and bombs, two million Khmers, 1/4th of the nation’s population, sought refuge in Phnom Penh.

When the Khmer Rouge seized power in April of 1975, they recognized the looming threats of mass starvation and the potential U.S. bombing of the city. They also sought to settle the score with Khmers who had been allies of the puppet Lon Nol regime.

While the evacuation of the city included excesses and political reprisals, it was also a strategic response. When hundreds of thousands died from starvation, the international media (meaning U.S.-dominated media) blamed the Khmer Rouge for all of the deaths.

To properly understand what occurred under the Khmer Rouge, it is necessary to examine the international and historical context at the height of the misnamed “Cold War” that created a power vacuum the Khmer Rouge filled.

The Ideology of the Khmer Rouge

While the Khmer Rouge leadership claimed to act in the name of the peasantry, they themselves came from the very social class they most despised, the petty bourgeoisie (semi-privileged people who were not farmers or industrial workers and owned small amounts of property, such as a store).

In Brother Enemy, the War after the War, globalization scholar Nayan Chanda evaluates the brass of the Khmer Rouge. Pol Pot was a French teacher. Nuon Chea, “brother number two,” was educated in Thai, French and Khmer and went to the prestigious Thammasat University in Bangkok. Ieng Sary, “brother number three,” went to college in Paris. “Deuch”, the notorious head of S-21 prison, was a school teacher. Pol Pot’s wife, Madame Khieu Ponnary, born into the Cambodian elite, studied at both French and English universities and was a respected authority on Khmer philology (the study of literary texts and linguistics).

Pol Pot, a former Buddhist monk himself, also appealed to the Khmer masses’ identification with Buddhism. Pol Pot manipulated the Buddhist precept, “nothing is lost, only transformed,” repeating to the peasant protagonists of genocide: “to preserve you is no gain; to destroy you is no loss.” S21 warden Deuch demanded obedience, impressing upon his largely illiterate peasant guards: “those who can read, read for others: it is forbidden to speak or to whisper to each other. You just shut up.”

The chief ideologues of Khmer Rouge received some Marxist training while working with the French Communist Party as students in Paris in the 1950’s, and were also influenced by China’s Cultural Revolution.

However, the Khmer Rouge significantly diverged from past revolutionary experiences, adopting their own ideology that divided society into “the new people” and “the old people.” They defined anybody tainted by Western, colonial culture as “the new people.” The vast majority of Khmers — who toiled the land and had never traveled to the city, studied or been exposed to outside influences — then became “the old people.” According to the twisted, anti-Marxist logic, they slated many who fell into the category of “the new people” for annihilation by “the old people.”

Historians and U.S. foreign policy experts such as Michael Vickery, John Barron, Anthony Paul and Noam Chomsky estimate that the number of executions were actually a far lower percentage of total deaths than we are told.

This is not an apology for the Khmer Rouge but rather an attempt to unmask all the parties involved in the holocaust.

Hell on earth

Pol Pot and his sanguinary bureaucracy — employing sheer terror and narrow-nationalism — envisioned a “pure,” agricultural society that would return the land of the Khmers to its “past greatness.”

Nationalists to the core, the Khmer Rouge commanders and bureaucrats spoke in the name of a mythical doctrine, a “Great Leap Forward to pure communism.” They abolished money, property and even cities.

The Khmer Rouge were anti-intellectual; they destroyed books and libraries and vowed to wipe out literacy. History did not exist. 1975 was Year Zero.

Anyone who opposed them or didn’t fit into their vision — city people, the educated, ethnic Vietnamese, former socialist cadre with training from the Indochinese Communist Party, Buddhists and soldiers who resisted orders — were rounded up and butchered.

The Khmer Rouge leadership wielded centuries of despotism, impoverishment and exploitation to monopolize power and forge their own view of what a “utopian” society should look like.

If the architects of genocide were true to their own perverse vision, they would have annihilated themselves first. Their loyalty, however, was not to a coherent ideology or to the unity of the oppressed social classes and forward-thinking intellectuals but to a monopolization of power based on the extinction of anyone from a social class that could challenge their hold over society. They reasoned that the peasantry was the only trustworthy class because they had nothing to lose and were too short-sighted to challenge their monomaniacal vision.

Genocide survivor and traditional bokator (an ancient form of Khmer martial artsmaster, Ros Serey, explained the demented social cleansing program to the author in the Village of Kabeyrey, in the northwest of Cambodia.

“We were teachers, well-versed in our traditions and the world. But after April of 1975 we had to pretend to be farmers. We pretended to be illiterate, lacking any culture. The Khmer Rouge targeted the sambo beb [which literally translated means “those with an abundance of manners].” This included anyone they considered petit-bourgeoisie. Anyone possessing worldly knowledge or any evolved language skills or culture was given an automatic death sentence. I saw thousands rounded up and slaughtered. I survived because I feigned ignorance. Silence was survival.”

In his essay, “The Diabolical Sweetness of Pol Pot,” political refugee and novelist, Soth Polin evaluates the world view of the Khmer Rouge:

“With his words, Pol Pot simplifies society. Everything is reduced to caricature, to extreme polarities, to a puerile [infantile] Manicheanism [cutting the world into two] swathed in the finery of well-turned phrases. This is what is now denounced about the old way of life: its nuances, its richness, its plurality. On the future, only one kind of new man shall impose himself, crushing all these elements in order to be no more than a sort of specimen from which one could draw millions of identical copies.”

Antithetical to Marxism

Ruling class ideology conflates the Cambodian genocide with communism. One of the most influential sources of this anti-socialist narrative is Yale University’s Cambodia Genocide Project (CGP). Working in collaboration with the State Department and the Royal Government of Cambodia. the CGP tells a version of history beneficial to the U.S. and their Khmer hirelings.

The retrograde vision of Khmer Rouge was, in fact, antithetical to Marxism. Marxist class analysis divides society into social classes, according to an individual’s relationship to the means of production. The vast majority of people in society are workers, who operate the factories, airports, bakeries, hotels etc. Workers produce the wealth of society but do not own this wealth. A tiny minority — the capitalist class — owns the means of production and the tremendous wealth that millions of workers produce. This is the central contradiction of class society. Marxists critique and believe in overthrowing this boss-worker relationship which is based on exploitation. The Khmer Rouge’s thesis of “the new versus the old people” was an opportunistic misapplication of classical communist philosophy.

Marxism strives for the elevation of the laborer and the oppressed above exploitation to the highest summits of knowledge, culture and freedom. By striving to free labor from exploitation, communism celebrates and fosters everyone’s individuality, or creativity. Individuality is not the same as individualism, the philosophical view that one person is more important than everyone else or the collective. Individuality refers to the liberation of one’s energy from out under the infernal capitalist system. José Martí, the historic Cuban writer and military leader, wrote about picking up the rake by dawn and the pen by dusk to capture the breath of man and woman’s existence.

The Khmer Rouge hurled Cambodia back centuries, targeting the intelligentsia, artists and anyone influenced by progressive ideas. As the reader heard from two previous testimonies, professors, writers and intellectuals had to feign ignorance and pretend to be illiterate peasants just to survive. For four years, another accomplished novelist, Chuth Khay, pretended to be deaf and mute and sold bread in hopes that no one would recognize him.

Yes, the old ruling royal class needed to be crushed but the Khmer Rouge also crushed creativity, culture and life itself. Though camouflaged in bizarre rhetoric, the crimes were no less dastardly.

The insane, possessed petty bourgeois tyrants rounded up and slaughtered thousands of others, just because they were doctors, engineers and other professionals. When the Socialist Republic of Vietnam intervened, and halted the Cambodian holocaust, the Khmer Rouge could not send their wounded soldiers to the hospital because they had killed all the doctors and turned the hospitals into torture centers.

Internationalism versus Hyper Nationalism

Another lynchpin of Marxism is internationalism. There are no borders in the workers’ struggle, as the old internationalist slogan goes.

The Khmer Rouge originally grew out of the Indochinese Communist Party, led by Ho Chi Minh, which sought to achieve independence from French rule for the three Indochinese nations: Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. The Khmer Rouge guerilla army emerged as a national force after working shoulder-to-shoulder with the NLF against the invaders and their stooge General Lon Nol.

A turning point came in the 1960’s. Turning their backs on Indochinese unity and internationalism, the Pol Pot group, pushed the irredentist myth of returning Kampuchea to its past glory and defined the Vietnamese, not Western imperialism, as the Khmer people’s principle enemy.

Xenophobes and isolationists led the Khmer Rouge. Instead of targeting the U.S. invaders and the old ruling class, the Khmer Rouge also blamed the Vietnamese for Kampuchea’s social ills.

This attitude grew out of a certain historical reality. The Cambodian-Vietnamese relationship was fraught with national tensions, with the Vietnamese traditionally seen as bullies. Centuries before, Vietnamese emperors had swallowed up large swaths of what was greater Kampuchea. The Khmer Rouge utilized this composite history to carry out wanton massacres of Vietnamese communities. Overall, more than 30,000 Vietnamese were massacred by the Khmer Rouge, along with entire villages accused of giving refuge to Vietnamese sympathizers. A widespread campaign of distrust and discrimination against the Vietnamese continues to this day in Cambodia.

Given the history of Western colonialism in South East Asia, the author was surprised to hear peasants in 2017 warn of pending Vietnamese domination. From an anti-imperialist view, how could it not be clear who really destroyed the country and who continues to be the chief threat to Southeast Asia today?

Who Executed Orders?

The Khmer peasantry produced the foot soldiers who carried out the Khmer Rouge’s retrograde, murderous vision. Like the long-oppressed Hutus in Rwanda, the Khmer peasantry were whipped up into a frenzy by chauvinists.

What was the historical experience of the Cambodian people?

They were Usurped for centuries by Vietnamese emperors. Next came nearly a century of French colonialism which functioned through the foreigner’ local asset, Lon Nol. A beleaguered people was then displaced and slaughtered in the millions by Nixon and Kissinger’s “secret” bombing sprees. The disaffected Khmer masses, humiliated and hungry from birth, formed the human material that was led to believe they were settling a historical score. When the proverbial, colonized and anguished chickens came home to roost, they devoured everything in their path.

There were other factors at play the museums leave out. Cambodia was a poor, war-devastated, colonized country without a developed industrial economy. At the time of the capture of Phnom Penh, there were only 150 trained doctors in the entire country. Droughts and the burning of the countryside by U.S. bombs severely affected the rice harvests. Due to fierce state repression under Lon Nol and factional disputes within the Khmer Rouge, there was a lack of trained cadre to carry out a cohesive, forward-looking economic and social policy. From 1975-1979, many Cambodians died of malnutrition and curable diseases. The Yale Cambodian Genocide Project and others conveniently tallied up all of the deaths as genocide victims without exploring all factors at play. Ruling class think tanks do the same thing when discussing “collectivization,” or the “second Russian Revolution” in the Soviet Union in 1927.

The genocide then was the product of an extremist, xenophobic ideology that manipulated accumulated colonial frustrations. One cannot in good faith condemn the avenger, without condemning the original historical usurper. This is the context “The Killing Fields” genocide tourism leaves out. In Sarajevo, Bosnia, the West has sought to manipulate the context of the Srebrenica massacre in a similar way.

The Global Class Struggle

To further understand the Cambodian genocide it is necessary to understand Cambodia’s position in the international political context of the 1970’s.

Cambodia was a tragedy of the “Cold War” or what Marxists call the Global Class Struggle.

In 1962, the U.S. unleashed a genocidal war against the Vietnamese people dropping six million tons of bombs, napalm and explosives on the country in order to prevent the nationalization and unification of Vietnam’s economy. As was previously stated, between three and four million Vietnamese, Laotians and Cambodians lost their lives in the U.S. war of aggression. After pledging to cease the murderous bombing sprees in order to win reelection in 1972, Richard Nixon secretly began bombing Vietnam’s two neighbors, Laos and Cambodia. The National Liberation Front’s (the NLF) supply lines, known popularly as the Ho Chi Minh trail, and their bases extended across Vietnam’s borders. The NLF was called the Vietcong by the U.S. media and the CIA to dehumanize the resistance, similar to what they do in Occupied Palestine today. The bombing in Cambodia had an incalculable cost for the civilian population. Millions of peasants were uprooted from their homes and forced into Phnom Penh.

If Yale University’s CGP wanted to accurately gauge the stretch of the holocaust, they would begin by focusing on the original holocaust, the U.S.’s holocaust of Vietnam and its neighbors.

Students of history are correct to ask: if there had not been a U.S. genocide in the three Indochinese countries, would a genocide have developed in Cambodia?

History is neither counter-factual, nor anti-factual.

The Chinese-Soviet split

The lack of principled global revolutionary leadership and unity also impacted Cambodia and Southeast Asia. The unprincipled Sino-Soviet split caused immeasurable damage to the world revolutionary movement. Both parties, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the Chinese Communist Party, failed to prioritize internationalism over petty border squabbles, a history of Soviet chauvinism and the Soviet’s defensive, non-revolutionary foreign policy.

The Chinese also reneged on their formerly principled foreign policy. As the Vietnamese waged a heroic defense of their homeland and defeat of the U.S. war machine in the early 1970’s, the Chinese hosted the world’s two biggest war criminals, Kissinger and Nixon, at secret meetings. Because of Chinese prejudices and Cold War realpolitick, the Chinese formed an anti-Vietnamese alliance with the Khmer Rouge.

By 1977, the Pol Pot grouping spoke of a “final solution” to the Vietnamese “problem,” planning to exterminate all the Vietnamese in Cambodia and to attack its long-time neighbor. In the spring of 1978, the Khmer Rouge penetrated the Vietnamese boarder and carried out indiscriminate slaughters of thousands of Vietnamese, both within Cambodia and over the border. Reeling from three decades of war against the French colonizers and the U.S., the last thing General Nguyen Vo Giap and the Vietnamese wanted was another war. However, they had no choice but to defend themselves. The embattled Vietnamese trained an anti-Khmer Rouge insurgency and marched on and occupied Phnom Penh in January 1979. Within a matter of six days, the Vietnamese intervention halted the genocide and sent the Khmer Rouge, who lacked popular support, scampering over the Thai border.

The campaign by the Vietnamese armed forces and the hastily trained Kampuchean United Front for National Salvation was necessary in this context and reflected yet another chapter of Vietnam’s self-sacrificing internationalism.

The U.S.-Chinese Alliance

The U.S. and China did not approve of Vietnam’s intervention.

Aligning with the U.S., Deng Xiaoping and the new Chinese leadership, having defeated the left-wing of the Chinese Community Party, falsely defined the Soviet Union and Vietnam as Southeast Asia and all of humanity’s principle enemy. Straying away from the Mao-era practice of genuine internationalism, the Chinese failed to admit the death-dealing, non-Marxist path Democratic Kampuchea (the Khmer Rouge’s name for Cambodia) had embarked upon. Obsessed with the Soviet Union and Vietnam and what they falsely termed “hegemonism,” China, in coordination with arch anti-communist U.S. National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, armed and supported the Khmer Rouge as an anti-Soviet proxy.

When the new premier Deng Xiaoping met with President Jimmy Carter at the White House in 1979, “the good Christian” and “human rights advocate” Carter gave China the go-ahead to invade Vietnam “to teach them a lesson” and to support the Khmer Rouge by funneling supplies to them through Thailand.

In a March 1979 interview with Time, Deng Xiaoping stated:

“We cannot tolerate the Cubans to go swashbuckling unchecked in Africa, the Middle East and other areas, nor can we tolerate the Cubans of the Orient [the Vietnamese] to go swashbuckling in Laos, Kampuchea or even the Chinese border areas.”

In response to the escalating hostility with its one-time conqueror (Chinese emperors ruled Vietnam for 800 years), the Vietnamese government initiated an anti-Chinese campaign and rounded up many Chinese families who had lived in Vietnam for generations. This further intensified the already frayed relationship. The historic Workers’ States that we defend and admire were behaving in anti-worker and anti-internationalist ways.

On February 17th, 1979, a quarter of a million Chinese troops poured into Vietnam in retaliation for Vietnam’s intervention in Cambodia. A one-month war left the north of Vietnam once again demolished. The Chinese invasion of Vietnam is a tragic anecdote in the history of the relations between two Workers’ states.

Another CIA proxy war

The necessary Vietnamese intervention would have been the end of Pol Pot’s army if it were not for Chinese and American backing.

Historian and Cambodia expert, Michael Haas’ Genocide by Proxy: Cambodian Pawn on a Superpower Chessboard documents what few Americans could imagine. For years, the Reagan and Bush administrations secretly supported the terrorist Khmer Rouge guerrilla army in order to oppose the new, Vietnam-backed Cambodian regime. The U.S. insisted that the Khmer Rouge be recognized as the legitimate representative of the Cambodian people in the United Nations from 1979 to 1993. John Pilger’s documentary, “Year Zero,” revealed the role of the U.N. in backing the Khmer Rouge insurgency.

A trove of half a million diplomatic cables released by wikileaks in May of 2015 showed that despite recognizing the “Pol Pot regime as the world’s worst violator of human rights,” the U.S. supported the Khmer Rouge.

Author Gregory Elich documents that by 1985, the CIA had sent $12 million to the Khmer guerrilla factions and Congress openly sent them $5 million in aid. Under “the Trading with the Enemy Act,” the same legislation it used to blockade Cuba, the U.S. imposed an economic embargo to strangle Vietnam and pressured other Western European nations to isolate the very government that halted the genocide.

The Indian journalist and historian Nayan Chanda unravels this complex and tragic history in Brother Enemy: the War after the War.

There was a reason Pol Pot was never prosecuted for the holocaust; in the end he was a proxy of U.S. foreign policy. Imperialism, a myth-making machine, never offers this context to us in the United States. How much easier to believe all of the savagery is distant from and foreign to us.

This is the same game plan Washington followed in Nicaragua, Mozambique, Afghanistan and across the world during the Global Class Struggle and more recently pursued in Syria and Libya, backing archaic, murderous thugs to carry out dirty wars against undesirable regimes.

Politicizing holocausts

The imperialists have politicized the meaning of the word holocaust. Ask any classroom of American students what comes to mind when they hear the term holocaust and they will mention the Nazi’s barbaric killing of 6 million Jewish people in Germany and the surrounding countries of Europe. Some may mention Cambodia or Rwanda. Very few students will also mention the 6 million non-Jewish people that the Nazis killed including socialists, union leaders, the elderly, Roma people, homosexuals and the disabled. Still fewer American students will remember that 27 million Soviets lost their lives to the Nazi war machine in defense of their homeland. 8 out of 10 Nazis who were killed were killed by humany’s heroes, the Soviets.

The colonization of the Americas was founded upon the two most far-reaching genocides in history, the slaughtering of indigenous nations and the enslavement of African nations. The Reagan regime carried out mercenary wars in Central America and Southern Africa in the 1980’s that left millions dead and displaced. There are no lack of U.S.-engineered holocausts.

The corporate media and standard curricula applies a tremendous double-standard by elevating some genocides and ignoring others. No where is this clearer than in Palestine.

Imperial double-standards

The same double standard also applies to the war criminals who carry out genocide. Pol Pot and Hitler are infamous, household names, as well they should be, because of the murderous crimes they committed. But George Bush, Tony Blair and many other functionaries oversaw the complete dismemberment of Iraq which led to millions of deaths. Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama have overseen the partition and recolonization of Libya and a horrific proxy war against and recolonizatoin of Syria which have also resulted in a massive death toll. Netanyahu and the settler, apartheid state of Israel displaces, genocides and occupies Palestinians every day.

The ruling class decides who is a war criminal and who is a hero.

Why doesn’t the U.N. set up an international tribunal to try U.S. war criminals?

The Cambodian tragedy shows once again that the American version of justice is not even-handed, it is a one-armed bandit.

“Deuch,” the warden of the nefarious Tuol Sleng prison, is the most celebrated case of a torturer prosecuted and sentenced to jail. Working with the Royal Cambodian government and relying on Yale’s distorted CGP research, the U.N. set up the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), commonly known as the Cambodia Tribunal or Khmer Rouge Tribunal. The Americans and the British ensured that there was only a token “search for justice.” Fearing that the world would learn about their role in the holocaust, the U.S., Britain and the U.N. state-managed the entire tribunal. One of the Cambodian lawyers involved insisted:

“All the foreigners involved have to be called to court, and there can be no exceptions…Madeleine Albright, Margaret Thatcher, Henry Kissinger, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan and George Bush…we are going to invite them to tell the world why they supported the Khmer Rouge.”

The ECCC of course prevented this from ever happening.

A Disservice to History

The Killing Fields Museum touches upon none of the dense history shared here. The elites of today who gloat about “the end of history” prefer facile, anti-communist clichés to concrete, dialectical analysis. How convenient to put all the blood on a lone “communist.” The truth is that Pol Pot betrayed the core principles of communism, acting out of paranoia and narrow nationalism and within the context of an unfolding genocidal war U.S. imperialism had already set in motion.

Plunging deep into now declassified imperialist diplomatic and military maneuvers and the intricate state-to-state relationships that existed in 1978-79 demonstrates who the real architects of genocide were. The Cambodian genocide shows us that there are no shortcuts to understanding the past. Pol Pot was not the only one with the blood of millions dripping from his hands.

Almost five decades later, imperialism conveniently erases all context, highlights the horrors and blames the very system it most fears, socialism. They also neglect to mention that it was the Socialist Republic of Vietnam and socialist Khmer, anti-Pol Pot rebels, who made the ultimate sacrifices and intervened to put an end to the holocaust. Inverting the heroes and murderers, the U.S. and their lackeys in Cambodia today continue to rewrite history.

Stirring up Necessary Ghosts:

A Return to the Killing Fields